Make Sure Your Buy-Sell Agreement Fits Your Business Model-reprinted with permission of Today’s CPA

With each passing year, more CPAs in public practice will be searching for an acceptable exit strategy. Most CPAs practicing in public accounting are in smaller firms and that segment of the profession is facing a myriad of succession planning problems. One major challenge facing many of these smaller firms is that of using the appropriate buy-sell or retirement agreement for the firm, based on the firm's business model.

Some firms are trying to use retirement agreements that simply do not and cannot work properly because of the firm's business model. Although every firm's retirement policy, and related buy-sell agreements are likely to have some unique qualities, there are some practices that are more commonly associated with different business models in use throughout the profession.

We categorize the two predominant business models in use among CPA firms as either the "Eat What You Kill" or "silo" model, and the "Building a Village," or "one-firm concept" model. The "Eat What You Kill" model focuses on a partner's production, book, chargeability, and realization as if the partner was running his/her own practice within a practice. The "Building a Village" model focuses on the firm's strategy and aligning all of the partners to not only achieve the strategy, but to also develop and leverage their people, follow firm policy, and be paid for performance that aligns with what is best for the firm. As a result of the differences in these business models, it

is logical that retirement policies would be radically different in their design.

THE EAT WHAT YOU KILL (EWYK) BUSINESS MODEL

Under the EWYK business model, the focus is on each partner's production - his/her clients, his/her book, new business generated, and the like. This model allows the most autonomy for partners because they are often free to conduct their practice as they please, perhaps within some very broad parameters. Thus, one of the advantages of this model is that a partner has a great deal of freedom in client and project selection, billing and collections, developing and delivering service offerings, and the degree of leverage used to perform the services (leverage is defined as the ratio of "all partner billed time to total billed time on a partner's book" of client relationships). Under this model, partners' common defenses as to why firm policies needed to be violated are embodied in rationalizations like:

- "Following the policy was not in the best interests of my client,"

- "The client wasn't willing to go along with our policy,"

- "My clients are unwilling to pay in 60 days so I allow them 90 before I contact them for payment."

In this model's hierarchy of importance, taking care of a client or satisfying a partner's whim has a higher priority than taking care of the firm.

Although in the typical EWYK firm, it's about "my" clients, my book, my processes, my policies, and so on, at some larger and more sophisticated firms using the EWYK model it may appear in some respects that they are operating under a Building a Village (BAV) or one-firm model. They have firm-wide mission, values and vision statements that present a unified image for the firm. They also likely utilize firm-wide hiring and other human resources practices. They may even have some firm-wide policies and procedures to which they attempt to hold all partners accountable.

However, while many peripheral aspects of a firm's operation appear to be aligned with the BAV model, when you look under the hood, it is not uncommon to find that their real values and beliefs, embodied in their partner compensation system, are clearly focused on individual partner production. Along with that, a partner's personal influence and persuasive power in this type of firm rest in the size of the client book he/she manages. So, when we talk about business models, we are not referring to the model that it appears a firm is following, but rather, the model actually embraced by the partner compensation framework.

THE BUILDING A VILLAGE (BAV) BUSINESS MODEL

With the BAV business model, the focus is on the firm as a whole, and therefore on the partners' roles requiring them to fulfill the firm's strategy and support the firm's overall success. In other words, it's no longer about "my" clients, but about the firm's clients (and even who the firm wants as a client). Therefore, the term shifts from "my book" to "managed book" with the key differential in this terminology being that the firm can shift clients to any partner, anytime, anywhere. This model provides the infrastructure, governance, decision-making and accountability processes necessary to hold each partner individually accountable for his/her part in the firm's overall success.

Under a true BAV business model, the firm has a clear institutional identity; the partner group (or elected board if the firm is large enough to warrant one) determines the firm's overall direction and strategy, and charges the managing partner or CEO with achievement of the strategy. The CEO, in turn, holds each partner individually accountable for achieving specific performance metrics, which are aligned with the tactics and strategies within the overall firm plan. Thus, while managed book size, business development and individual partner production are still important considerations in a BAV firm, other individual performance targets, driven by the firm strategy, also play a big role. As well, in the BAV model, leverage becomes a much more important driver, which allows substantial growth in the average book managed by a partner. Under the BAV system, closing competency gaps at all employee levels within the firm, passing down work, managing the work rather than doing it, and freeing up partners' time to fulfill their "real" partner roles (regularly getting in front of "A" clients, managing client relationships, following firm policy and achieving strategy) are paramount.

BUYOUT, RETIREMENT AND BUSINESS MODEL

So why does all of this matter ? Quite simply, it makes a big difference in what a retiring partner is selling and what the remaining partners are buying. In the succession management survey we created with Private Companies Practice Section (PCPS) in 2012, we found that multi-owner CPA firms are using three main methods to calculate a partner's deferred compensation or retirement benefit:

- partner's book;

- partner's share of equity multiplied by firm's average net annual revenues;

- multiple of partner's salary.

If your firm is functioning as an EWYK firm, using partner's book of business to set a partner's retirement in most instances would be appropriate for you. For those operating in the BAV model, either the partner 's share of equity times revenues or the multiple of salary would likely be the most appropriate. However, we see the greatest conflicts and disconnects in situations where a partner wants the privilege of using a retirement benefit formula inconsistent with the business model actually in place. For example, it is common for us to see a partner operating in an EWYK environment who wants to use the benefit model as if they were working under a one-firm or BAV model. Common signs that you are operating in an EWYK environment are when partners individually decide:

- which firm policies they will follow and which policies they will ignore;

- which clients and what types of work they'll take on;

- how much to bill clients and when to collect once (and if) the work is billed;

- whether or not they'll develop anyone else in the firm;

- what services they will perform regardless of whether the services are of strategic value to the firm;

- what services will be offered, or not offered, to each client;

- if and how they will transition client relationships upon retirement;

- when they want to retire, often with no fixed dates for sale of interest and no requirement to provide notice in advance to the firm when they do decide to leave;

- to what degree they will allow themselves to be held accountable to some overall firm direction, governance and management.

We often find that these same partners who want to run their own silo'd business within their firm also feel entitled to fixed, agreed-upon retirement benefits payable to them, regardless of the fact that:

- they are leaving a book of work that perhaps no one else either wants to do, knows how to do, or has the time and capacity to devote to it;

- they have not built any bench strength in the people below them (in their opinion, it's the firm's fault for not having hired "experienced" people);

- they've not adequately leveraged their book through the use of effective delegation to others;

- many of their clients will be up for grabs when they depart, leaving the firm without a significant amount of annuity relationships from which to pay the retirement benefit.

THE CASE OF HOPALONG, CASSIDY AND SUNDANCE, CPAS

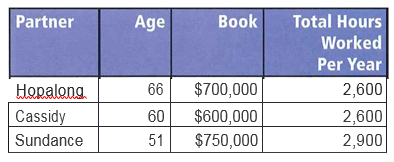

Let's take an example compiled from many real-life situations to help further paint the picture here. Assume that Hopalong, Cassidy and Sundance are equal partners in their firm. They've been in business together for decades. Following are some key statistics on each of them.

The partners have been able to achieve some degree of specialization in their work together. Hopalong is the tax partner of the firm, and while he oversees some accounting engagements, he gets Cassidy involved for quality control on them. Cassidy does mostly audit work, and most of her audit work is done for small governmental agencies and some nonprofit organizations. Hopalong can help with the tax returns for the nonprofits, but tells people proudly that he hasn't created an audit workpaper in years. Meanwhile, the youngest of the three partners, Sundance, can perform both tax and audit work, although he readily admits he's not very strong in the audit side of the house.

Although they've worked hard at building a strong firm, they've had trouble hanging on to good staff over the years, so they're a little short when it comes to managers and supervisors. They do have some lower level people, and some good seniors. They manage to keep them all pretty busy with the work they have on hand. You can see from their book size and total hours worked (of which very little time is devoted to, or recorded for, nonchargeable activities), that they don't use a lot of leverage in their work.

So what's going to happen if and when Hopalong finally decides he wants to retire? Sure, they have an agreement in place that says he's entitled to about $600,000 paid out over 10 years based on his current book, but who will take on the clients he's arguably leaving behind? One of the two remaining partners doesn't really do much tax work, and neither of the remaining partners has the capacity (let alone enough unencumbered hours in the day) to take on Hopalong's book, even if they wanted it.

And what about Cassidy? Although Cassidy may decide to retire before Hopalong, who within the firm is going to take over the work she's been doing? With the firm being short on qualified people who could be developed quickly for a transition, it doesn't appear that the firm could actually retain the books on which Hopalong's or Cassidy's deferred compensation is based.

It should be obvious that a common fixed buy-sell and/or deferred compensation arrangement makes no sense in this situation. What this firm should have is not a BAV buy-sell and deferred compensation arrangement, but rather a right of first refusal. Under this type of arrangement, the firm and its remaining owners are not required to buy out the retiring partner. The partner is free to sell his/her book under whatever terms can be negotiated with the other owners within the firm. And we would recommend that this kind of purchase be based on client retention, not a fixed price paid up front. Should the departing partner not find the offers of his/her partners to be sufficient he/she can look outside the firm for buyers, and the firm and remaining partners will have a first right of refusal after the partner obtains a bona fide offer from an outsider.

This represents the best option for both the buyers and the seller. The buyers get to negotiate which clients they wish to take on, at what price, and the seller has the freedom to manage his/her practice in any reasonable manner, toward whatever consequences come with those business decisions when it's time to pull the trigger on an exit strategy. In other words, since the other owners had little say about the services the retired partner offered, what clients were in his book, what pricing and other arrangements he worked out, how he did his work (through developing people and leverage), and no stick to require the appropriate transition of clients, then why would the remaining owners have any responsibility to take on the departing partner's book and carry the debt burden for it? So only the "purchased book option based on retention'' makes much sense for the firms that are still very heavily EWYK-oriented. And to be fair, if the firm has been operating in a fashion similar to our case study above, then the retiring partner should have the option to sell his/ her book outside the firm because being paid based on retention when the other partners don't have the requisite skills, capacity or support infrastructure would likely be a financial disaster for the retiring partner.

Of course, if your firm is operating under a true BAV model, then coming up with a fixed formula, often based on the two methods introduced above (partner's share of equity times revenues, or some multiple of salary) makes a lot more sense, because the investments and structure have been put in place to force the partner to build and manage a book consistent with the firm's strategy and to build the capacity to work the book.

OPTIONS AVAILABLE

Until now, much has been said in the profession about succession planning and helping smaller firms through the succession management maze. Unfortunately, in most cases, more has been said than has been done. And just as unfortunate, too many of those discussions include senior partners demanding retirement benefits they are not entitled to, given the business model they are operating under. But the good news is that there are plenty of fair options available to firms of every size.

If you choose the EWYK business model, then set up your governance, processes and retirement agreements to align with that. If you choose the BAV model, then make sure your processes and agreements fit that model. And if your firm has one foot in the EWYK model, and the other in the BAV model, then decide which you want to follow and make the necessary changes so that you will be fully operating in one or the other. By doing so, you will be able to better align partner expectations, accountability and benefits fairly and consistently. You will also be positioned to sustain a successful, profitable firm long into the future.

Bill Reeb, CPA, CITP. CGMA and Dom Cingoranelli, CPA, CGMA, CMC™ are co-founders of Succession Institute, LLC, a management consulting firm that specializes in helping CPA firms determine strategy, manage succession, create accountability,and more. Their books, articles, video webcasts, competency model, and draft partner agreements represent leading edge tools and intellectual property they have created to support best practice changes CPA firms desire to implement.

| File |

|---|

| Make Sure Your Buy-Sell Agreement Fits Your Business Model |